This blog is cross posted from CG Space.

Economies are exposed to myriads of external risks such as production variability from climate shocks, volatility in global commodity prices, fluctuations in foreign investments, among other risks. For instance, climate change, a key determinant of production variability, continues to dominate the global risk landscape posing a long-term threat to the global economy. As the severity, frequency and unpredictability of extreme weather events increase, uncertainty over availability of food, commodities, and labor increases, in turn, impacting investment, consumption and trade at a macro level.

According to World Bank 2021, it is estimated that over 70% of natural disasters in Kenya are attributable to extreme weather events. Major droughts occur approximately every ten years, and moderate droughts or floods every three to four years. This repeated patterns of floods and droughts in the Kenya have had adverse socio-economic impacts. The world bank estimates economic impact of droughts at 8 percent of GDP every five years. ND-GAIN Index[1] also recognizes Kenya as vulnerable to climate change impacts, ranked 144 out of 185 countries included in the estimation. Going by these facts, Kenya, like other developing countries, remains highly vulnerable to climate-related physical, transition, and liability risks. However, mitigation and adaptation strategies remain limited (Grippa, Schmittmann and Suntheim, 2019 ; Bank of International Settlements( BIS), 2021a[2])

As the impacts of climate change become more pronounced, tackling it requires collective efforts by all parties. The Paris Agreement[3] -which entered into force for Kenya in 2017-sets a center stage for countries to deal with the impacts of climate change, and to make finance flows consistent with a low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient pathway. This means that financial institutions, and by extension the central banks face increasing pressure to address the associated climate related risks to monetary policy, financial stability, and the broader economy. Thus, it presents an opportunity for the central banks to develop comprehensive strategies and policies that enable the banks to integrate these risks into their frameworks for resilient financial, and that economic is maintained.

Key questions arise for the central banks to respond to climate related risks:

- How does the central bank effectively identify, assess, and mitigate these climate-related risks to the Kenya’s financial system?

- What changes in the supervisory and regulatory frameworks are needed without compromising the central bank’s traditional mandates of price stability and economic growth?

- How do central banks promote sustainable finance and support the transition to a low-carbon economy?

The first important step is to have evidence of a country’s economywide risk profile i.e. the size of risks and the level of an economy’s exposure. In this step, two fundamental questions are addressed: One, how vulnerable is the economy, and population to risks? Two, which sources of risk are most important for different development outcomes?

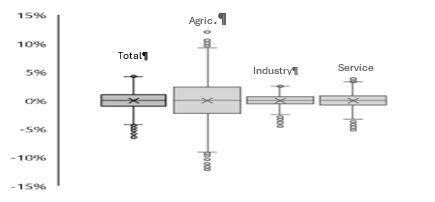

While assessing Kenya’s economywide risk profile, (Channing Arndt et al, 2024) found that Kenya’s economy is exposed to external risks. As shown in Figure 1 below, total GDP fluctuates about positive/negative five percent (±5%), relative to trend in any given year. At a sectoral level, agriculture sector is the most exposed to risk as is shows the largest deviation relative to trends.

Figure 1: Deviation in total GDP and by sectors (in % relative to trend)

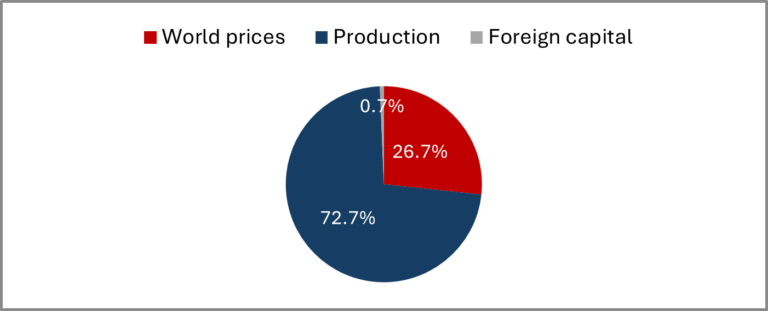

The assessment also suggests that production risks dominate the variations seen in total GDP. Figure 2 below shows that production risks accounts for 73% of the GDP variation.

Figure 2: Sum of individual contributions (% share of total GDP)

Results also indicate that Consumption is more exposed than GDP with low-income households being most exposed. Notable fluctuations also reflected on trade balance given a shift in world prices and foreign investment inflows. Regarding national poverty headcount rates, the findings indicate fluctuations of about positive/negative four percentage points (±4%) from the trend in any given year. Similar result is also shown in the Kenya’s population prevalence of undernourishment. This reflects disproportional impacts of climate change mostly on vulnerable people who are already facing hunger and food insecurity. The extreme climate related risks exacerbate exposure to food insecurity and undernutrition to already vulnerable group.

What opportunities does this Kenya risk profile assessment present to Central bank of Kenya?

The results points to reducing vulnerability to agrifood production risks as a priority policy for Kenya. Adopting production technologies and practices that narrow production uncertainty, diversifying production away from more risky production and towards less-risky food crops and increasing yields of certain crops to offset the impacts of negative risks.

In this case, the Central Bank of Kenya (CBK) can incorporate climate risk evidence tools into its policy framework. These tools ensure that both the supply-side and demand-side policy measures implemented by the CBK to promote economic, social, and environmental resilience are fully integrated.

Considering that policies prioritization is unavoidable, identification of the most cost-effective strategy is crucial. This would require more analysis of the agrifood system investment costs and benefits, and projections on how the economy is expected to evolve (e.g., urbanization, income growth, dietary change, among other factors).

To address the challenges of external risks to the economy and population, opportunities for more evidence tools is needful. In this regard, on July 8, 2024, CBK and International Food Policy Research Institute(IFPRI) signed MoU at CBK office in Nairobi, Kenya. The partnership is aimed at co-creating evidence for CBK’s decision making. Hence, this collaboration is under the CGIAR Initiative on National Policies and Strategies (NPS) in promoting the role of science in policy making.

[1] University of Notre Dame (2020). Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative. https://gain.nd.edu/our-work/country-index/

[2] Bank for International Settlements (BIS). (2021a). Climate-related Risk Drivers and their Transmission Channels. BIS, Basel, Switzerland

[3] United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change,” The Paris Agreement,” December 2015 (https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement/the-paris-agreement).

Authors

Lensa Omune, Research Officer, IFPRI Kenya

Juneweenex Mbuthia, Research Officer, IFPRI Kenya

Photo credit: Central Bank of Kenya Communications team